My Rusty Christmas: How Rust earned a place next to C++, Java, Python and Go (and made me argue with rust traits)

Every few years, a new language earns a permanent place in your toolkit.

Not because it’s fashionable.

Not because the internet says you should.

But because, at some point, you realise:

“This actually solves problems I already have — even if it annoys me first.”

This Christmas, Rust joined that list for me.

The starting point

My background is pretty broad:

-

~10 years of C++ (systems, performance, RAII, undefined behaviour as lived experience)

-

A lot of Java (enterprise, scale, long-lived systems)

-

Plenty of Python (glue, speed of thought, experimentation)

-

Some Go (services, pragmatism — the least of the four)

Rust had been circling my radar for years. I admired it conceptually, but like many C++ developers, I had the usual thought:

“This looks nice, but I already know how to do this safely.”

So this Christmas, I stopped theorising and just started to actually build.

What I expected vs what happened

What I expected:

-

A steep learning curve

-

Many compiler errors

-

A lot of clever ideas wrapped in friction

What actually happened:

-

A steep learning curve

-

Many compiler errors

-

…and a growing suspicion that the compiler was usually right

A very early example:

It felt like a very opinionated code reviewer who had seen all my old mistakes before.

1let a = String::from("hello");

2let b = a;

3// println!("{a}"); // ❌ compile error

4In C++, this would compile and later explode.

Rust just says “no” — immediately, and for a good reason.

Rust didn’t feel like a new paradigm.

Ownership and borrowing: fewer lies, more honesty

The big shift was ownership and borrowing.

At first it feels restrictive.

Then it doesn’t feel very pleasant.

Then — slowly — it feels honest.

1fn len(s: &String) -> usize {

2 s.len()

3}

4let s = String::from("hello");

5let n = len(&s);

6println!("{s}"); // ✅ still validNo more casual aliasing.

No more “this reference should be fine”.

No more mental bookkeeping about who frees what and when.

Coming from C++, this didn’t feel like losing power — it felt like formalising discipline I already tried to apply manually.

Error handling without drama

Rust’s error model clicked faster than expected.

-

Errors are data

-

Failure is explicit

-

Control flow is visible

1fn read_config() -> Result<String, std::io::Error> {

2 let content = std::fs::read_to_string("config.toml")?;

3 Ok(content)

4}The ? operator alone deserves a small shrine.

It reads exactly like what it does:

“If this fails, stop here — cleanly.”

After years of C++ exceptions and Go’s if err != nil, this felt like the grown-up version of both.

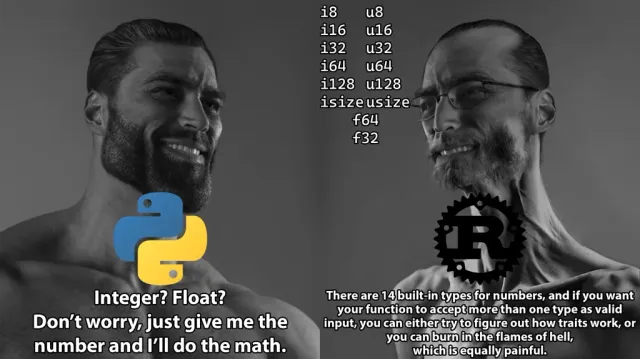

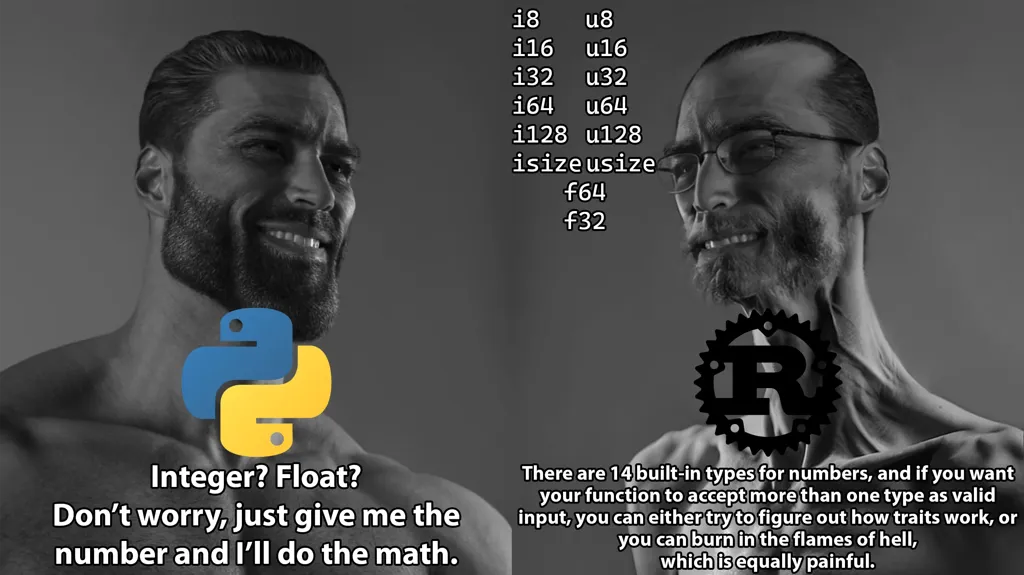

And then… numeric traits happened

At some point during Christmas, I made the classic mistake.

I wanted to write a simple function that “just works for numbers”.

Python brain said:

1def add(a, b):

2 return a + bRust replied:

1fn add<T>(a: T, b: T) -> T {

2 a + b

3}

4// ❌ nopeSo I specified what Rust wanted:

1use std::ops::Add;

2fn add<T: Add<Output = T>>(a: T, b: T) -> T {

3 a + b

4}Then I wanted to mix types.

1add(1i32, 2.0f64); // ❌ still nope

2At some point, I found myself staring at trait bounds thinking:

“I have written template metaprogramming in C++.

Why is this harder than I expected?”

This is where that Rust numeric meme hits painfully close to home.

If you want “numbers” in Rust, you don’t get a free abstraction.

You get:

-

traits

-

bounds

-

associated types

-

crates like num

And the creeping realisation that this is deliberate.

The uncomfortable realisation

Then it clicked.

Rust isn’t bad at numeric abstraction.

It’s refusing to lie.

Python says:

“I’ll figure it out at runtime.”

Rust says:

“Tell me exactly what you mean, or don’t ship.”

So you end up writing:

1fn add_as_f64<A: Into<f64>, B: Into<f64>>(a: A, b: B) -> f64 {

2 a.into() + b.into()

3}Yes, that’s more explicit.

Yes, that’s more friction.

But it also means:

-

no silent truncation

-

no implicit widening

-

no platform-dependent behaviour

-

no “this worked in tests but not in production” math bugs

I didn’t enjoy that realisation in the moment.

But I respected it.

Undefined Behaviour (UB), now with fences

After enough years in C++, you don’t fear crashes.

You fear the bugs that only show up in production.

Rust’s stance on UB is refreshingly blunt:

1unsafe {

2 let p = 0xdeadbeef as *const i32;

3 println!("{}", *p); // UB lives here, clearly marked

4}Yes, UB exists.

No, you don’t get it accidentally.

If you want it, you must opt in explicitly.

That changes how you think about boundaries — and about trust.

Async without a GC (still slightly magical)

Async Rust deserves its own article, but briefly:

1async fn fetch(url: &str) -> Result<String, reqwest::Error> {

2 let body = reqwest::get(url).await?.text().await?;

3 Ok(body)

4}-

async/await without a garbage collector

-

Futures as explicit state machines

-

No runtime hiding memory costs

Yes, the borrow checker gets louder here.

Yes, you sometimes have to restructure code.

But the result is predictable performance with compile-time safety, which is still rare.

From Christmas experiment to actual work

The real signal wasn’t intellectual.

This didn’t stay a holiday experiment.

Before Christmas was over, I was already using Rust in a ZEN Software project — not as a rewrite for fun, but where Rust’s strengths actually fit:

-

correctness

-

performance

-

long-term maintainability

That’s usually the moment a language stops being interesting and starts being useful.

Where Rust sits in my toolbox now

I don’t think in terms of replacement.

For me, it now looks like this:

-

Java→ stability, scale, predictability

-

Python→ speed of thought, experimentation

-

Rust → correctness under constraints, without giving up performance

-

Go→ pragmatic services

-

C++ → ultimate control, legacy ecosystems, sharp edges

Rust didn’t make me feel less experienced. It made me feel like my experience finally had a compiler that backed me up — even when it annoyed me.

Closing thoughts

I didn’t “switch” to Rust this Christmas.

I added it.

Yes, I argued with traits.

Yes, I cursed numeric bounds.

Yes, I lost a few hours to the borrow checker.

But the result stuck.

2026 is going to be a bit more Rusty.

And I’m genuinely looking forward to it. 🦀

Optimize with ZEN's Expertise

Upgrade your development process or let ZEN craft a subsystem that sets the standard.

Read more:

My Rusty Christmas: How Rust earned a place next to C++, Java, Python and Go (and made me argue with rust traits)

Every few years, a new language earns a permanent place in your toolkit. Not because it’s fashionable. Not because the i...

Why I Keep Coming Back to Games: Two Books for the Beach (or Poolside)

Summer 2025 Poolside reading: must-read books about working in game development ...

AI is the missing piece of the Productivity Puzzle

Today, I’d like to plea that Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the missing piece of the productivity puzzle, revolutionizi...

Threads vs Twitter: The Social Media Battle of the Decade - Who Will Emerge Victorious

In a fierce social media showdown, Meta's CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, delivered a mighty kick to ‘Chief Twit’ Elon Musk. The b...

Banning ChatGPT from your workplace?

Innovations such as ChatGPT and AI have begun transforming industries, enhancing productivity, and reshaping our work. H...

Poolside reading - 'Blood, Sweat & Pixels' and 'The Masters of Doom'

My reason for being in the software industry has always been games; from an early age, I played games on my XT-PC, Gameb...